IndexFiguresTables |

Kyungbo Lee and Young-Bae KoClass Imbalance in UWB-Based Backward Driving DetectionAbstract: Backward driving in highway Hi-Pass lanes poses serious safety risks due to limited space and sudden maneuvers. This study proposes a deep learning framework that classifies forward and backward driv- ing using Ultra-Wideband (UWB) Channel Impulse Response (CIR) data. Experiments conducted in a re- al tunnel environment show that a narrow segment of the CIR sequence was found to contain the most discriminative features for direction detection. To ad- dress this limitation, the concept of the Discriminative Signal Ratio (DSR) and analyze the impact of class imbalance. CNN, LSTM, and Transformer models are compared under varying class ratios, and results show that oversampling the minority class at a 1:6 ratio yields optimal performance. The findings demonstrate the feasibility of CIR-based direction detection and provide insights for future deployment in intelligent transportation systems. Keywords: UWB CIR, backward driving detection , class imbalance , DSR , deep learning Ⅰ. IntroductionTraffic accidents remain a critical threat to road safety, with backward driving incidents in highway Hi-Pass lanes known to cause severe rear-end collisions. In Korea alone, approximately 180 such cases were reported over the past five years, highlighting a pressing need for real-time detection and response mechanisms[1]. This issue is particularly urgent in constrained environments like Hi-Pass lanes, where driver confusion or transponder malfunction can lead to abrupt backward movement. To address this problem, this study proposes a backward driving detection method based on Ultra-Wideband (UWB) Channel Impulse Response (CIR) data. UWB technology provides fine time resolution and robustness against multipath interference, making it well-suited for dynamic vehicular applications, as demonstrated by recent UWB-based contactless gate systems and pedestrian localization for autonomous vehicles,[2,3]. Recent research has applied deep learning to UWB CIR data, primarily focusing on classifying line-of-sight (LOS) and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) conditions[4,5]. Other approaches, such as Doppler-based motion estimation[6], show promise but lack direction-specific information. However, these works have rarely addressed real-time direction recognition, and often assume balanced datasets-overlooking the challenge of natural class imbalance in backward driving, where such events occur far less frequently than forward driving. This study classifies forward and backward driving using CIR data collected in a real highway tunnel. Convolutional Neural Networks(CNNs) extract local spatial patterns, while Long Short-Term Memory(LSTM) and Transformer models capture temporal dependencies. By varying the backward-to-forward sample ratio, the impact of class imbalance is analyzed, revealing saturation points where additional data offer limited benefit. The proposed framework demonstrates the potential of UWB CIR data for real-world vehicle behavior classification and provides insights into model robustness and data sufficiency under naturally imbalanced scenarios. Ⅱ. Experiments and Data Analysis2.1 Experimental Setup and Data CollectionAs shown in Fig. 1, the UWB CIR data used in this study were collected at the Tunnel Safety Test Site managed by the Korea Expressway Corporation. The objective was to analyze the difference in UWB CIR signals between forward and backward driving conditions. While it would be ideal to collect data from various road environments, this study utilized a tunnel test site, which offers a controlled yet highway- equivalent and safe environment. Specifically, the data were collected under the speed limit of 30 km/h, as allowed in the Hi-Pass lanes, ensuring that the experiment reflects realistic highway conditions while maintaining a controlled and repeatable test setup. The experiment used a UWB module compliant with IEEE 802.15.4a, supporting high-precision ranging and low-power communication. UWB tags were mounted on vehicles, and anchors served as fixed receivers. CIR data were collected every 100 ms, with each reception consisting of 1016 amplitude samples. To compensate for the limited number of runs, Gaussian noise and amplitude scaling were applied for data augmentation. The experimental setup is summarized in Table 1. Table 1. Experimental Setup and Specifications

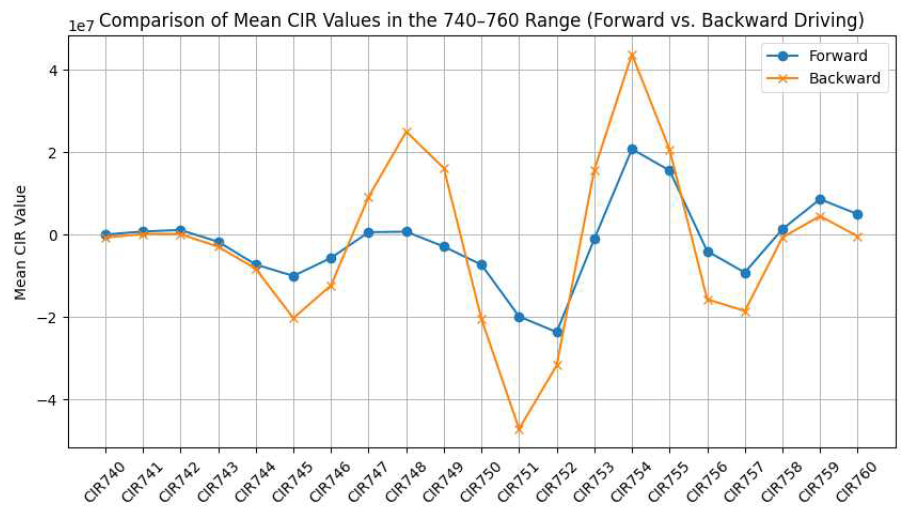

2.2 CIR Data AnalysisAmong the 1016 indices in the CIR sequence, the segment from index 740 to 760 exhibited the most significant variation between forward and backward driving in terms of average signal amplitude. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the signal patterns diverge sharply within this range, particularly around indices 746-751 and 754-755. For instance, CIR751 shows an almost inverse trend depending on the vehicle’s direction. These findings suggest that direction-specific multipath reflections are localized and concentrated in specific CIR indices. This observation highlights the presence of a narrow but discriminative region within the CIR sequence that carries meaningful information for direction classification. The rest of the sequence remains largely redundant or noise-prone with respect to the task. 2.3 Discriminative Signal Ratio and the Need for Class Imbalance CompensationBuilding upon the above observation, only a small portion (approx. 11 out of 1016 indices) serves as an informative region. Although comprising only 1% of the CIR sequence, this segment dominates the learning process. To quantify this, we define the Discriminative Signal Ratio (DSR) as:

For instance, if k = 11, then DSR ≈ 0.0108 (1.08%). In such a setting, the effective learning region is extremely sparse. To ensure sufficient exposure of this region during training, the minority class (i.e., backward driving) must be oversampled. Empirically, a ratio of 1:2 to 1:6 already shows performance improvement, while excessive oversampling yields diminishing returns―highlighting the existence of a saturation point. This finding aligns with the notion of the Effective Receptive Field (ERF) in CNNs, which states that although the theoretical receptive field expands with network depth, only a small, Gaussian-like central portion actually contributes to the output[7]. In the same spirit, the CNN in this study primarily focuses on a narrow band of CIR features during learning, making class imbalance a critical factor-especially for rare events like backward driving. To effectively learn from such sparse discriminative regions, a larger volume of minority class data is necessary to ensure sufficient exposure during training. Ⅲ. Experiment Results and Analysis3.1 Model Design and ImplementationThis study implements and compares three deep learning models-CNN, LSTM, and Transformer-for classifying forward and backward driving using UWB CIR data. Each model was chosen for its strength in capturing spatial or temporal patterns in sequential signals. · CNN: Effective for extracting localized spatial features (e.g., energy peaks and decay) in CIR, especially within the narrow discriminative region (indices 740-760). · LSTM: Suitable for modeling temporal dependencies in CIR sequences reflecting vehicle motion over time. · Tr ansformer : Utilizes a self-attention mechanism to capture both local and global patterns, making it robust to sparse informative signals. All models were implemented in TensorFlow and trained on 1016-point CIR sequences. To address class imbalance, the backward-driving class was augmented and evaluated across ratios from 1:1 to 1:8 using precision, recall, and F1-score. The CNN included two 1D convolutional layers (64 and 128 filters) with ReLU and max-pooling. The LSTM used a bidirectional layer with 128 units, and the Transformer consisted of two encoder layers with four heads and a hidden size of 128. All models ended with a dense layer for binary classification. Training was performed using the Adam optimizer (learning rate 0.001, batch size 128) with early stopping based on validation loss for up to 50 epochs. 3.2 Performance Comparison Across Models and Class RatiosTo evaluate the impact of class imbalance on driving direction classification, three deep learning models- CNN, LSTM, and Transformer-were tested with class ratios ranging from 1:1 to 1:8. The minority class (backward driving) was oversampled using Gaussian noise-based data augmentation to simulate imbalance scenarios. CNN showed the most consistent improvement as the backward-driving class was oversampled, reaching a saturation point at a 1:6 ratio with an F1 score of 80%. This suggests that CNN effectively captures local spatial features in the CIR signal, especially within the discriminative index range (740-760) critical for direction classification.LSTM showed moderate variability but also reached its peak performance (79%) at the 1:6 ratio, benefiting from its ability to model temporal dependencies across the CIR sequence. In contrast, Transformer models consistently underperformed across all ratios, with a maximum F1 score of only 58% at 1:6. This may be due to the attention mechanism’s difficulty in focusing on sparse informative regions in highly augmented data. Unlike CNN and LSTM, Transformer attention weights tend to dilute, reducing discriminative learning. These findings highlight the importance of the DSR, where only 1% of CIR indices are informative. CNNs are inherently well-suited to capture such localized signal features. Table 2. F1 Scores (%) Across Class Ratios (Forward: Backward)

Inference latency was also measured to assess realtime applicability. The average inference time per CIR sample was 0.72 ms for CNN, 1.16 ms for LSTM, and 2.21 ms for Transformer. These results confirm that CNN offers both the highest classification performance and the best computational efficiency, making it suitable for real-time backward driving detection. Unlike conventional UWB correlation-based methods that rely on peak detection or ToA estimation-both prone to multipath distortion and threshold tuning -the proposed learning-based framework offers greater robustness and adaptability. The CNN model effectively learns spatially discriminative features from raw CIR data without handcrafted design. All experimental results were obtained from actual vehicle tests in a controlled tunnel environment, not from simulations. This real-world validation confirms the feasibility and deployment potential of the approach in intelligent transportation systems. Ⅳ. Conclusion and Future WorkThis study demonstrated that CNN, LSTM, and Transformer models can effectively classify backward driving using UWB CIR data, even under class-imbalanced conditions. Only a small segment of the CIR sequence proved critical for classification, highlighting the importance of focused feature learning. Although validated in a tunnel environment, the model’s generalization to diverse conditions remains a challenge. Future work will explore adaptation strategies such as environment-aware feature selection and transfer learning to support broader deployment in intelligent transportation systems. References

|

StatisticsCite this articleIEEE StyleK. Lee and Y. Ko, "Class Imbalance in UWB-Based Backward Driving Detection," The Journal of Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences, vol. 50, no. 11, pp. 1683-1686, 2025. DOI: 10.7840/kics.2025.50.11.1683.

ACM Style Kyungbo Lee and Young-Bae Ko. 2025. Class Imbalance in UWB-Based Backward Driving Detection. The Journal of Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences, 50, 11, (2025), 1683-1686. DOI: 10.7840/kics.2025.50.11.1683.

KICS Style Kyungbo Lee and Young-Bae Ko, "Class Imbalance in UWB-Based Backward Driving Detection," The Journal of Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences, vol. 50, no. 11, pp. 1683-1686, 11. 2025. (https://doi.org/10.7840/kics.2025.50.11.1683)

|